Transcript

TEXT ON SCREEN: March 4, 2025

ARCHIVAL (THE WHITE HOUSE, 3-4-25):

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: To further enhance our national security, my administration will be reclaiming the Panama Canal, and we’ve already started doing it.

NARRATION: President Trump has aggressively reasserted U.S. influence in Latin America with the capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro. But since taking office, he’s also been threatening to take control of the Panama Canal.

The threats have reignited tensions between the U.S. and Panama, and revived a decades-old political debate over who should control the canal.

Sixty years ago, one flashpoint in that debate would change the course of U.S. and Panamanian history . . .

ARCHIVAL (ASSOCIATED PRESS, 12-30-64):

NEWS REPORT: Panama broke relations with the United States. Relations were not restored until the U.S. promised to re-examine the status of the Canal Zone.

NARRATION: . . . and it started with an argument between high school students.

ALAN MCPHERSON (PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY): You’ve got a very small event that turns into an international crisis.

NARRATION: In the 1960s, decades after the U.S. secured the right to build and run a shipping canal across Panama, thousands of Americans lived in the area around the canal, known as the U.S. Canal Zone.

ALAN MCPHERSON: Life in the U.S. Canal Zone in the 1960s is something that’s almost out of time. It looks like “Leave It to Beaver.” Single-family homes, pristine green lawns.

ARCHIVAL (NBC NEWS, 1962):

NEWS REPORT: What the Canal Zone residents have done is to re-create a tiny slice of America on the Ninth Parallel. The morning paper is the Panama American, in English. Movies and television shows are a little late in coming, but 100 percent American.

JIM JENKINS (FORMER STUDENT, BALBOA HIGH SCHOOL): The Canal Zone was a wonderful place to grow up in. Since it was all government-controlled, the government took care of all facilities. They had planted fruit trees among the buildings. We had mangoes and lemons and limes and things like that. If I wanted a mango, I could go to a tree and pick a mango. It was idyllic.

ARCHIVAL (CBS NEWS, 4-26-76):

NEWS REPORT: It is just like a U.S. town, complete with U.S. laws, U.S. lawmen, the American flag and the Little League.

JIM JENKINS: When you grow up in the Canal Zone…

ARCHIVAL (NBC NEWS, 1962):

NEWS REPORT: I pledge allegiance to the flag…

JIM JENKINS …you understand the greatness of the people who built it, and it instills a sense of pride in what America can accomplish.

ALAN MCPHERSON: The Americans who live on the Canal Zone are called Zonians, and they really see themselves as defenders of this outpost of U.S. power.

NARRATION: But outside the Canal Zone, life was very different, and there was growing anger about what many young Panamanians viewed as an American colony on land they thought should belong to them.

DR. RIMSKY SUCRE (FORMER STUDENT, INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PANAMÁ, TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): The Zonians were a people who didn’t want to speak Spanish, who felt superior, who were arrogant.

NARRATION: Rimsky Sucre and Pablo Mudarra went to high school just outside the Canal Zone, and they could see the mango trees planted by the Americans.

PABLO MUDARRA (FORMER STUDENT, INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE PANAMÁ, TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): We can’t go and pick the mangoes. No, no, it’s the Canal Zone. It belongs to the gringos. That was a feeling of dislike that grew in me, like, [bleeped expletive], oh, I can’t go and pick something up in my own territory. At no time were we free. We lived under the North American umbrella.

NARRATION: Their school, El Instituto Nacional de Panamá, was becoming a center of anti-American activism, and the students had one main demand.

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): What we wanted was to be able to raise the Panamanian flag in the Canal Zone territory, which was a yearslong struggle.

NARRATION: After years of rising tension, the U.S. government agreed: It would officially fly both flags together in the Canal Zone.

But after the Zonians protested, the Zone governor decided that no flags would be flown at some buildings, and took down the American flag outside Balboa High School, where Jim Jenkins was a student.

JIM JENKINS: That just didn’t sit right with me. Being an American school with American students, we wanted our American flag. The suggestion was made, why not just raise the flag at the school to demonstrate what we want?

ALAN MCPHERSON: And they stay there day and night for one or two nights. But then it gets complicated when the Panamanians hear of this protest.

TEXT ON SCREEN: JANUARY 9, 1964

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): It was the last official day of classes and we have not gone to put the flag in the Canal Zone. We have to go put up the flag.

NARRATION: Around 200 Panamanian students marched from the Instituto Nacional to Balboa High School, carrying a historic flag from their school.

ALAN MCPHERSON: It’s actually a flag that had been used in anti-U.S. protests in 1947. The flag itself is considered pretty sacred.

PABLO MUDARRA (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): We asked our principal for it and he told us, care for it a s if it were your life. Don’t let anything happen to the flag.

NARRATION: The Zone police allowed a delegation of six students to approach the flagpole.

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): I decided to climb the tree with a little Panamanian flag, with the idea to be able to see what happened. Many students from Balboa High School and many parents booed them and they also started singing the U.S. national anthem.

JIM JENKINS: They wanted to show their flag. We explained we could not put their flag up because we didn’t want their flag up instead of ours, and we really couldn’t put two flags up at the same time without putting one underneath the other, and that’s not going to happen either. Somewhere along the line, something happened, and the police pushed them off.

NARRATION: The Panamanian students were surrounded. A scuffle broke out and the flag was torn.

ALAN MCPHERSON: It’s really not clear what happens or who does it.

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): Classmates, angry and crying, came back to us. And what happened? They tore the flag. They tore our flag. And what do we do? What can we do?

PABLO MUDARRA (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): We had put up with a lot. That! That was going to be the last straw.

NARRATION: The Panamanian students ran out of the Zone. By the time they got back to Panama, crowds were already starting to form.

PABLO MUDARRA (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): So, that’s when we started to grab cars with white license plates from the Canal Zone. We turned them over and set them on fire.

ARCHIVAL (EFOOTAGE, 1-13-64):

NEWS REPORT: The rioting went on far into the night as the offices of U.S. business establishments were looted and burned.

ARCHIVAL (ABC NEWS, 9-5-77):

NEWS REPORT: It was an outburst of violent nationalism unprecedented in Panama’s history. The students were outraged, and the government of Panama claimed it was unable to control them.

ALAN MCPHERSON: Panama’s own National Guard does nothing. The commander of the Guard actually said later on, if we had gone in there and stopped the rioters on the first day, they would have turned against us.

NARRATION: That night, mobs tried to force their way into the Canal Zone and shots were fired.

ALAN MCPHERSON: There are many eyewitnesses who saw Zonian policemen shooting into groups of Panamanians.

PABLO MUDARRA (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): And there – there you didn’t even have to aim at anyone. Every time we heard the bullets whistling, you could only go, my God! Don’t let it be me.

ALAN MCPHERSON: You have Panamanian snipers getting on top of buildings in Panama, shooting into the Canal Zone, and most of what the U.S. Army is doing is counter-sniping, trying to sort of shoot snipers who are shooting at them.

NARRATION: Amid the chaos, one of Rimsky Sucre’s friends was burned by a tear gas canister.

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): I wanted to take him to the hospital. So he and I got into one of those little buses. When we arrived at Santo Tomás Hospital cars arrived and later ambulances, and they brought bodies of dead people. I wasn’t prepared for that.

NARRATION: The violence went on for nearly four days. By then, four American soldiers and 21 Panamanians were dead. Hundreds more were injured. Investigators would find hundreds of bullet holes in Panama and the Canal Zone.

Jim Jenkins became the face of the flag protest. He was called a monster in the Panamanian press, and left the country at the end of the month.

RETRO REPORT PRODUCER: Do you feel any responsibility for what came out of your protest?

JIM JENKINS: Of course. Our intent was just to get our flag back at our school. If I hadn’t participated in the flag raising, if we hadn’t done that, what would have happened? It’s hard to say.

NARRATION: The violence was a turning point. Panamanians now demanded more than just having their flag in the Canal Zone.

RIMSKY SUCRE (TRANSLATED FROM SPANISH): We want total sovereignty in the Canal Zone. That was the change that took place.

ALAN MCPHERSON: The Panamanians decide that what they really want is the canal and the end of the Canal Zone. Once they have made that demand, it’s really impossible for anyone to sustain political leadership in Panama without pushing that demand further.

NARRATION: In the U.S., the riots had convinced the Johnson administration that it was untenable to control the canal, and started the process of negotiating a new treaty.

But the idea of giving up U.S. territory was controversial, and negotiations went on for nearly 14 years, over four presidential administrations. Many conservatives, including Ronald Reagan, argued that giving up the canal would be a sign of weakness and would make the U.S. a laughingstock.

ARCHIVAL (1976 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN, 1976):

RONALD REAGAN: The Panama Canal Zone is sovereign United States territory just as much as Alaska is, as well as the states carved from the Louisiana Purchase. We bought it, we paid for it, and General Torrijos should be told: We’re going to keep it.

NARRATION: But in 1977, a different view of America’s role in the world won out. Panamanian leader Omar Torrijos and President Jimmy Carter signed a treaty that would, for the first time, give Panama control over the canal and Canal Zone, at the end of 1999.

ARCHIVAL (JIMMY CARTER PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM, 4-18-78):

PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER: These treaties can mark the beginning of a new era in our relations not only with Panama, but with all the rest of the world.

ALAN MCPHERSON: Carter, he understands that Panama has become a symbol for all of Latin America, and so he essentially wants to advance friendship with all Latin Americans with this concession.

ARCHIVAL (JIMMY CARTER PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM, 9-7-77):

PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER: Fairness, and not force, should lie at the heart of our dealings with the nations of the world.

NARRATION: But the treaty had an important caveat: the U.S. had the right to intervene militarily to protect the canal, and it has become a flashpoint again.

ARCHIVAL (WAAY 31 NEWS, 2-2-25):

DONALD TRUMP: We’re going to take it back, or something very powerful is going to happen.

NARRATION: Trump’s rhetoric has led to turmoil and anger in Panama, where January 9th remains a symbol of the Panamanian fight for independence, 60 years after the confrontation at Balboa High School.

ALAN MCPHERSON: What is the real endgame for the United States? Is it concessions, or is it really getting the canal back? If it’s getting the canal back, I think Trump and his secretary of state, Marco Rubio, are really misreading the psychology of Latin America, and specifically of Panama. Put simply, there would be a high price to pay.

(END)

How a 1964 Student Protest Reshaped the Fight Over the Panama Canal

A student protest in 1964 exposed a deeper struggle over sovereignty and control of the Panama Canal.

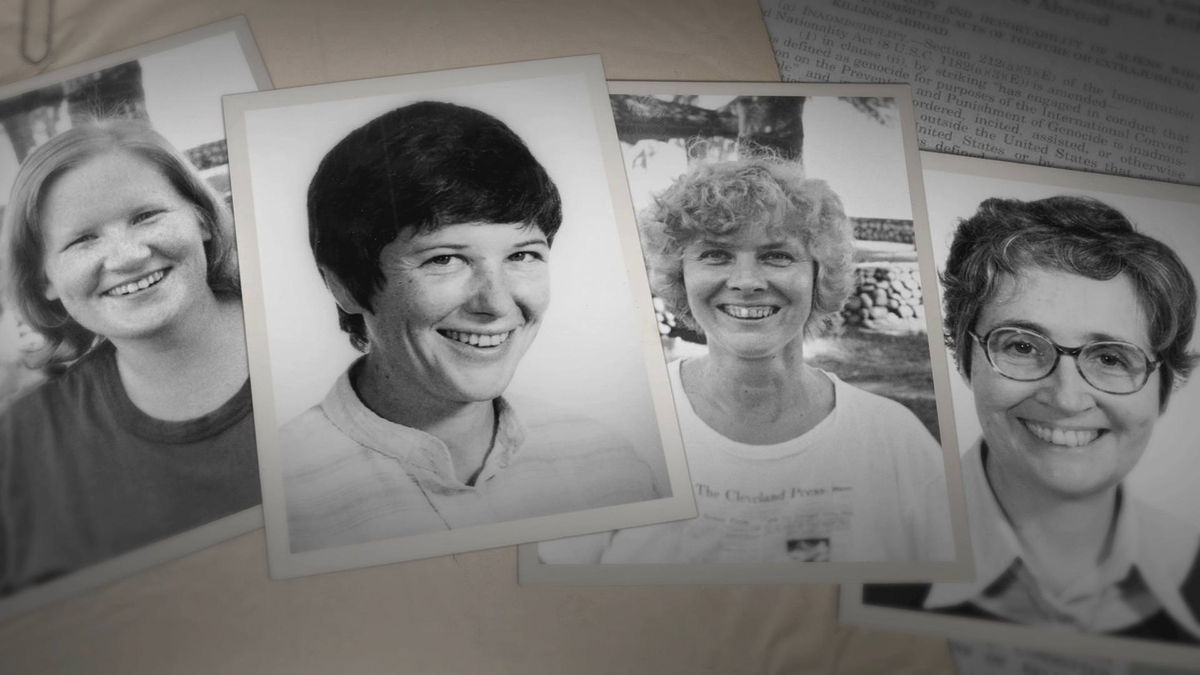

A dispute between American and Panamanian high school students over which country’s flag to fly escalated into days of violence, leaving more than 20 people dead and shattering relations between the United States and Panama. The clash grew out of a struggle over who should control the Panama Canal and the U.S.-run Canal Zone that cut through the center of the nation.

This film traces the roots of that crisis, showing how Americans’ lives inside the Canal Zone fueled growing anger among Panamanians who lived outside the zone.

Drawing on eyewitness accounts and archival footage, the film shows how a symbolic fight over national identity became a turning point that reshaped diplomacy, amplified demands for sovereignty and eventually led to treaties that transferred control of the canal to Panama. The story helps explain why debates over American intervention and influence in Latin America still resonate today.

- Producer: Scott Michels

- Editor: Brian Kamerzel