Transcript

Click here for the full video page and educator materials.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

JANUARY 25, 1942

THE DAY OF CLEO WRIGHT’S LYNCHING

HARRY HOWARD: The day the lynching happened, you all must’ve been totally surprised and shocked.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Oh, man. Yes. Cleo, he was a real handsome-looking guy. Remember him just well. He had a whole life ahead of him, big ball player.

HARRY HOWARD: He was well-known in the community?

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: He was well-known in the community. Yeah, that’s rights, because he was a very friendly person. We all really liked him a lot, and he had a beautiful wife. Her name was Ardella Gay, and she was pregnant then, little kid. It was so sad. Man, that was sad.

RHONDA COUNCIL: I’ve heard a couple of different versions of what happened, so I really don’t know the truth. One version that I’ve heard was he broke into this white lady’s house. He apparently tried to attack her. The second version was that maybe he had a relationship with the lady, and she didn’t want nobody to find out about it. I don’t know.

MIKE JENSEN: The story of Cleo Wright is extremely complex. You can speak to someone else, and their version of the story can differ. And I certainly can’t dispute them, and nor can they dispute me.

Cleo worked at the Sikeston Cotton Oil Mill. The fastest way to get home would be to walk down the railroad track, but Cleo went three streets over to Kathleen and entered a home, the home of Sarge and Grace Sturgeon. At some point, there either was a confrontation or an argument, and Cleo pulled a knife out, stabbed Grace in the stomach, and severely, severely injured her.

CAROL ANDERSON (AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES PROFESSOR, EMORY UNIVERSITY): The police and the neighbors come running. They find Cleo Wright, and as they’re putting him in the police car, he’s fighting. He’s fighting really hard.

MIKE JENSEN: The police officer working at the time was a gentleman named Hess Perrigan. Cleo pulled a knife and stuck it into Hess Perrigan’s mouth. Hess turned around and, with his .45 revolver, shot Cleo four times.

CAROL ANDERSON: They take him to the whites-only hospital. Then, as it’s getting light, they’re like, you can’t be here because you’re Black. And he’s clearly dying.

MIKE JENSEN: This location right here was City Hall. It was also the courthouse. It was also the jail. Police took Cleo down to a holding cell, which was right on the main level basically by the front door.

CAROL ANDERSON: The townsfolk are milling about because what has happened to Grace Sturgeon has riled up the white community, and they began to break down the door to the jail.

MIKE JENSEN: The crowd surged forward and pulled Cleo out of that cell and drug him off of the steps of the City Hall. They hooked his ankles around the bumper of the car, and they took him down to a location in Sunset, took some kerosene, and poured it on the body and lit the body on fire.

CAROL ANDERSON: As his body is on fire, church service is going on. People are running into the church going, oh, my God. They are burning a Black man. They are burning a Black man.

MIKE JENSEN: The body remained out there all day on that Sunday. The procession of cars going down Malone Avenue simply to see that was virtually bumper to bumper. It was a brutal, morbid spectacle.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: I said, Daddy, we better get out of town. They’re setting Sunset on fire. And police is, is everywhere. I just wanted to leave. And, but Daddy kept saying, we’re not going no place, and we’re going to be, live here. So, our house that night was just full of people sitting up, drinking coffee, and just not, don’t know what to do.

HARRY HOWARD: And they told me they picked up rocks and bricks and crowbars and just anything to protect our community.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Hm-hmm [affirmative]. Daddy got shotguns and everything else. It was a horrible time, and a lot of peoples left town. And they left they properties and everything, had their suitcase on the back of the cars. I was crying and everything else.

MIKE JENSEN: It’s difficult to wrap your mind around how people, civilized people, could put themselves in a situation where they would do something like that. To my way of thinking, you had a Black man clearly attacking a white woman. That was in white society’s mind, at least, the ultimate no-no.

CAROL ANDERSON: What you have coming out of the white community after this kind of cathartic explosion of violence is a retreat into the, you know—well, we’re civilized, and we’re not those kind of people. But we were driven to it.

MIKE JENSEN: Within every individual, within every community, there is good and there is evil. And on a late January day in 1942, evil ruled the day. They may have defined Sikeston, Missouri for one day, but they don’t define it for the history of this town.

The Lasting Impact of a Lynching

This excerpt examines the lynching of Cleo Wright in 1942, reflecting the racial violence and societal tensions of the time.

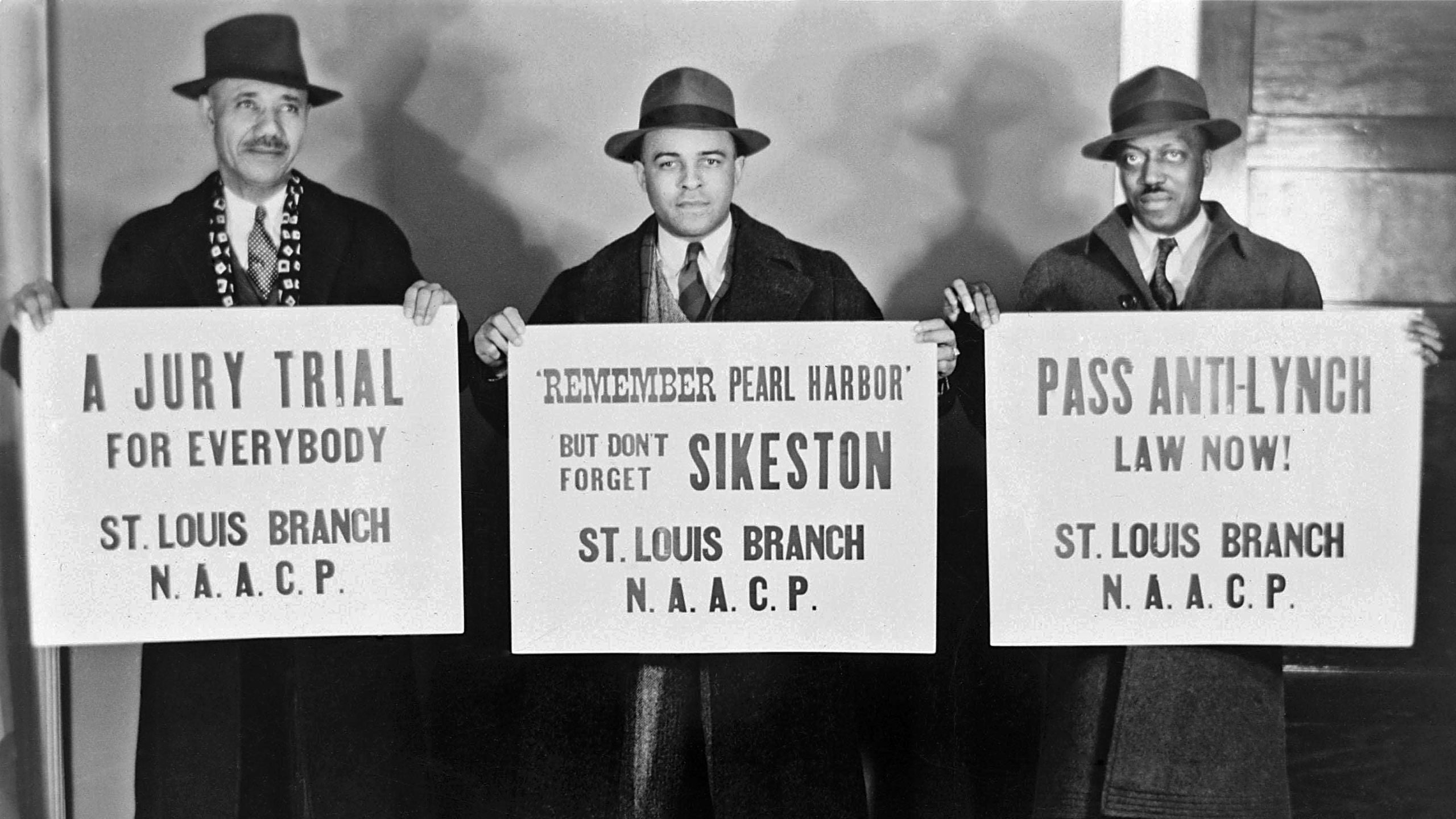

The lynching of Cleo Wright on Jan. 25, 1942, provides a vivid case study in historical memory. Following an altercation in Sikeston, Mo., Wright was taken into police custody. A mob forcibly entered the jail, removed him from his cell, and carried out a public lynching, burning his body. Witnesses recall widespread fear among Black residents. This episode is a window on the history of racial violence in the United States, its societal implications and its lasting effects on communities.

This is an excerpt from “Silence in Sikeston,” which is a co-production of Retro Report, WORLD and KFF Health News. To see more check out our “Silence in Sikeston” collection.

- Director / Writer: Jill Rosenbaum

- Reporter: Cara Anthony

- Editor: Cheree Dillon

- Editor: Brian Kamerzel

- Senior Producer: Karen M. Sughrue