Transcript

NARRATION: In Sikeston, Missouri, 1942, a 26-year-old Black man was lynched by a white mob.

PERSHARD OWENS: The fact remains that this African American man was burned in front of a church and we don’t talk about it.

MIKE JENSEN: It was a brutal, morbid spectacle.

CAROL ANDERSON: People are running into the church going, oh, my God. They are burning a Black man. They are burning a Black man.

HARRY SHARP: I did not hear about it from my parents or grandparents, ever. I asked them about it one time after I had heard about it, but it was not subject of discussion.

NARRATION: Almost 80 years later, another Black man died.

JEAN KELLY: Denzel deserved to live. He really did. He deserved to have a chance to live.

NARRATION: Their stories still haunt the community today.

LARRY MCLELLON: For years, I’ve said, you’re going to see one of our young men get shot down before long.

NARRATION: From Retro Report and KFF Health News, “Silence in Sikeston,” a special edition of Local, U.S.A.

RHONDA COUNCIL: This is a town of roughly 17,000 people, and if I had to take a rough guess how many Blacks here – 6,000 probably. There’s not a whole lot, but it’s enough.

All towns have the good stuff along with the bad stuff, and unfortunately something terrible happened here. If you were to ask anybody in their 20s, maybe 30s, about the lunching of Cleo Wright, probably couldn’t tell you. And I’m talking about people here in Sikeston. Not anywhere else. Here in Sikeston. I don’t know why it was a secret, but history can’t be erased. Even though that was over 70 years ago, the story needs to be told.

LARRY MCLELLON: Sikeston, they don’t know how to start the healing process. For years, I’ve said, you’re going to see one of our young men get shot down before long. And it wasn’t long after that Denzel did get shot down. This young man’s life did not have to be taken. This is the dark side of Sikeston.

TITLE:

SILENCE IN SIKESTON

RHONDA COUNCIL (GRANDDAUGHTER OF LYNCHING WITNESS): Yes, ma’am. I just remember hearing that this young man was lynched in Sikeston, and it was kinda hard to believe that that actually happened in this place that I grew up in. But it was never talked about in public. Just maybe with your family it was discussed. But other than that, you never heard the story about Cleo Wright.

MABLE COOK (LYNCHING WITNESS): I was young then. I just felt bad over it. I felt hurt. Hm-hmm [affirmative].

RHONDA COUNCIL: Nobody talked about it after it happened.

MABLE COOK: That’s right.

RHONDA COUNCIL: It was like it didn’t even happen.

MABLE COOK: Everybody, everybody said they wanted to get their mind off it. They didn’t want to think about nothing like that, but I think you should, you know, let somebody know something went on here.

RHONDA COUNCIL: The railroad tracks are gone right now, but they ran right along this area here. And this is where they came and they burned his body, right in front of the church right here.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON (LYNCHING WITNESS): We was just kids outdoors playing and talking, had a big police car come down the street hollering, saying, all the [BLEEP] better get off the street. Because—

HARRY HOWARD (CARLEEN HARRINGTON’S BROTHER): Are you serious?

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: It had a man’s leg tied to the back of a car, dragging him, and so, they had drug him from downtown across the railroad track. We was shocked. And you talking about just it was a horrible feeling.

RHONDA COUNCIL: Where were you at when it happened?

MABLE COOK: Standing on the porch. We heard all the commotion. So, me and my sister, we got on the porch and looked out, and we saw them dragging him. They could have just taken him and put him in jail or something and not do all that to him.

RHONDA COUNCIL: So, it was a message they was getting out?

MABLE COOK: Yeah. That’s right. They did that so the next one should know not to be trying to do the same thing see. Hm-hmm [affirmative].

TEXT ON SCREEN:

MAY 2021

A YEAR AFTER DENZEL TAYLOR’S DEATH

JEAN KELLY: Denzel died three months prior to his 24th birthday. He was still young, vibrant, and energetic, and had so much love for his children and his family and friends. And his smile was just amazing.

JEAN KELLY (IN CHICAGO, LOOKING AT PHOTOS): Who looks like him?

DENZEL’S SISTER 1: Oh, yeah. It is.

JEAN KELLY: Anaya?

DENZEL’S SISTER 2: Yup, just like him.

JEAN KELLY: Look at this picture. This was taken a year before his death. He was having trouble in school out here in Chicago, and after eighth grade when he went into high school, there were a lot of shootings and a lot of gang activity. And so, I was like, no. I don’t feel like you’re safe here in Chicago. So, we both agreed that he would go to Sikeston. His dad and his stepmom, they both said, okay, well, he can stay with us out here.

MILTON TAYLOR (DENZEL TAYLOR’S FATHER): Well, when he was 15, he moved in with me. I learned how to play, uh, how to play the 2K, how to play the basketball game, just to spend time with my son. Once he hit 21, it was, like, back and forth. He had his own family. They were at my house all the time.

DENZEL TAYLOR (ON FAMILY VIDEO) What is you doing, bubba?

MIKELA JACKSON (DENZEL TAYLOR’S FIANCÉE): We have three girls. We have our oldest. Her name is Deniya. He named her after him, of course. And then, we have our middle child. Her name is Ayana. And then, we have Brooklyn. I was actually four months pregnant with her when he passed away.

Our oldest daughter, she asks me all the time, where Daddy at? And she say, he sleeping. And it broke me down because no mother wants to hear their child say that about their dad. It’s heartbreaking.

AMUSEMENT PARK ATTENDANT: It’s time to pick a prize. Here we go. Let it roll.

MIIKE JENSEN (PUBLISHER, SIKESTON STANDARD DEMOCRAT, RETIRED): The story of Sikeston is not unique. It’s not unlike a lot of other little small towns in the Midwest or across the country. Founded in about 1860, kind of a Civil War kind of town. This is the northernmost point in the United States where cotton is grown. Does the South begin in Sikeston? You could almost make that argument. You really could.

I’m a lifelong resident of Sikeston, started a newspaper here, and was a publisher until 2019 when I retired.

HARRY SHARP (PASTOR, SMITH CHAPEL UNITED METHODIST CHURCH, RETIRED): Living in Sikeston, there have been seven generations of my family. This woman right here in the picture was my mother. My great-grandparents on my mother’s side to my great-grandchildren, they all contributed in ways that involve the community and it made me who I am.

When I was a kid, Sikeston was known as the town with more millionaires per capita than any town in the United States. We were not among them. We were on the edge of them.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

1950S

SIKESTON COTTON CARNIVAL PARADE

HARRY SHARP: Most of the uptown people had a patriarchal relationship with Black families. If they needed food, the family would help. If they needed medical help, the family would help. So, you knew each other. You know?

LARRY MCLELLON (CIVIL RIGHTS ADVOCATE): One of the first things that I point out to people when they come here is the history of Sikeston, Missouri. Sign says, “Sikeston, a white settlement, 1803.” It means hatery, hatery, bigotry. You name it. And this should actually be removed.

These tracks, it’s supposed to be the dividing line between Black and white. Back in the old day, when dark comes, you don’t want to be caught over here after 6:00. You want to be on this side of the tracks. This area is called Sunset Addition. This area is called white section of town.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Sunset started where the railroad track was.

HARRY HOWARD: So, most of the Blacks lived there.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Hm-hmm [affirmative].

HARRY HOWARD: Sunset, we had a movie theater, stores.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Plenty of stores. We had taxicabs, dry cleaners, all kinds of things.

HARRY HOWARD: And the whole area where you saw Lincoln School, so kind of a self-sufficient community.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Yes. Kids on the streets playing. Everything was just lovely as it could be for Black people.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

JANUARY 25, 1942

THE DAY OF CLEO WRIGHT’S LYNCHING

HARRY HOWARD: The day the lynching happened, you all must’ve been totally surprised and shocked.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Oh, man. Yes. Cleo, he was a real handsome-looking guy. Remember him just well. He had a whole life ahead of him, big ball player.

HARRY HOWARD: He was well-known in the community?

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: He was well-known in the community. Yeah, that’s rights, because he was a very friendly person. We all really liked him a lot, and he had a beautiful wife. Her name was Ardella Gay, and she was pregnant then, little kid. It was so sad. Man, that was sad.

RHONDA COUNCIL: I’ve heard a couple of different versions of what happened, so I really don’t know the truth. One version that I’ve heard was he broke into this white lady’s house. He apparently tried to attack her. The second version was that maybe he had a relationship with the lady, and she didn’t want nobody to find out about it. I don’t know.

MIKE JENSEN: The story of Cleo Wright is extremely complex. You can speak to someone else, and their version of the story can differ. And I certainly can’t dispute them, and nor can they dispute me.

Cleo worked at the Sikeston Cotton Oil Mill. The fastest way to get home would be to walk down the railroad track, but Cleo went three streets over to Kathleen and entered a home, the home of Sarge and Grace Sturgeon. At some point, there either was a confrontation or an argument, and Cleo pulled a knife out, stabbed Grace in the stomach, and severely, severely injured her.

CAROL ANDERSON (AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES PROFESSOR, EMORY UNIVERSITY): The police and the neighbors come running. They find Cleo Wright, and as they’re putting him in the police car, he’s fighting. He’s fighting really hard.

MIKE JENSEN: The police officer working at the time was a gentleman named Hess Perrigan. Cleo pulled a knife and stuck it into Hess Perrigan’s mouth. Hess turned around and, with his .45 revolver, shot Cleo four times.

CAROL ANDERSON: They take him to the whites-only hospital. Then, as it’s getting light, they’re like, you can’t be here because you’re Black. And he’s clearly dying.

MIKE JENSEN: This location right here was City Hall. It was also the courthouse. It was also the jail. Police took Cleo down to a holding cell, which was right on the main level basically by the front door.

CAROL ANDERSON: The townsfolk are milling about because what has happened to Grace Sturgeon has riled up the white community, and they began to break down the door to the jail.

MIKE JENSEN: The crowd surged forward and pulled Cleo out of that cell and drug him off of the steps of the City Hall. They hooked his ankles around the bumper of the car, and they took him down to a location in Sunset, took some kerosene, and poured it on the body and lit the body on fire.

CAROL ANDERSON: As his body is on fire, church service is going on. People are running into the church going, oh, my God. They are burning a Black man. They are burning a Black man.

MIKE JENSEN: The body remained out there all day on that Sunday. The procession of cars going down Malone Avenue simply to see that was virtually bumper to bumper. It was a brutal, morbid spectacle.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: I said, Daddy, we better get out of town. They’re setting Sunset on fire. And police is, is everywhere. I just wanted to leave. And, but Daddy kept saying, we’re not going no place, and we’re going to be, live here. So, our house that night was just full of people sitting up, drinking coffee, and just not, don’t know what to do.

HARRY HOWARD: And they told me they picked up rocks and bricks and crowbars and just anything to protect our community.

CARLEEN HARRINGTON: Hm-hmm [affirmative]. Daddy got shotguns and everything else. It was a horrible time, and a lot of peoples left town. And they left they properties and everything, had their suitcase on the back of the cars. I was crying and everything else.

MIKE JENSEN: It’s difficult to wrap your mind around how people, civilized people, could put themselves in a situation where they would do something like that. To my way of thinking, you had a Black man clearly attacking a white woman. That was in white society’s mind, at least, the ultimate no-no.

CAROL ANDERSON: What you have coming out of the white community after this kind of cathartic explosion of violence is a retreat into the, you know—well, we’re civilized, and we’re not those kind of people. But we were driven to it.

MIKE JENSEN: Within every individual, within every community, there is good and there is evil. And on a late January day in 1942, evil ruled the day. They may have defined Sikeston, Missouri for one day, but they don’t define it for the history of this town.

ANNOUNCER (AT A SIKESTON GATHERING): We’re going to play some music by some of the artists that will be performing next week.

JEAN KELLY: I always felt that Sikeston was a nice place to be because I, like, kind of, the country feel. I always thought of Sikeston being a safe haven for Denzel. I’ve heard a lot of times mothers say, oh, why did they kill my son? I could never say someone deserved to die. You know? But Denzel deserved to live. He really did. He deserved to have a chance to live.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

APRIL 29, 2020

THE NIGHT DENZEL TAYLOR WAS SHOT

MILTON TAYLOR: I can’t stop thinking what I could have done different to change the outcome of what happened that night. I had been drinking. Yeah. I’m sure I had been drinking. He came and talked to me, asked me for some advice on some personal things, and my advice was not what he wanted to hear at the time. I didn’t find out until a month later that he was heartbroken. He was, he was hurt. See, if I had known that, I wouldn’t have said the things I said to make him that angry.

MIKELA JACKSON: When Denzel called me, I said, you know, it’s two in the morning. What you need? And he was like, I need you to come get me. And in the background, I could hear his dad just full-blown just arguing.

MILTON TAYLOR: I told him to leave my house. It’s time for him to go. I’m not going to argue with you in my house. As I was closing the door behind him, he pulled a gun out.

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

LISA TAYLOR: Is the ambulance coming?

OFFICER: Yeah.

OFFICER: Who was it?

LISA TAYLOR: My stepson shot his daddy.

JEAN KELLY: After Milton was taken away in the ambulance and the police were still out on the property, Denzel ended up back at the house. He was standing there. He wasn’t doing anything. And then, when they turned the body cam on. . .

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

OFFICER 1: Show me your hands, now!

OFFICER 2: Take your hands out of your pockets.

DENZEL TAYLOR: Just kill me, bro

OFFICER 1: Now! [SOUNDS OF SHOTS FIRING]

OFFICER 2: We got shots fired! We need E.M.S.! We got one subject down, shots fired!

OFFICER 1: Hands now! Hands! Hands!

OFFICER 3: What’s in his pocket? Are you fucking serious?

OFFICER 2: Looks like a fucking stick of wood.

JEAN KELLY: Denzel was not armed. He didn’t pose a threat towards the police officers at all.

MIKELA JACKSON: I couldn’t believe it because it’s, like, how, how could you do a human being like that? Especially someone that was unarmed. I’m numb, but I’m more so angry because I’m the one that has to deal with my kids asking about their dad.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

ELKHART, INDIANA

HOME OF CLEO WRIGHT’S DAUGHTER

79 YEARS AFTER THE LYNCHING

NANNETTA FORREST (CLEO WRIGHT’S DAUGHTER): My mother, she was pregnant with me at the time that it happened. They tell me the people were so scared they were packing their luggage and they were getting out of there, and I don’t if we left right away or not. But I do know one thing. My mother never left her mother and dad. Everywhere Grandma and Grandpa moved, that’s where Mama moved to.

I was, like, 13, 14 before I even found out. So, I really don’t know a whole lot to tell. They had, uh, an old show that used to come on called Strike It Rich.

ARCHIVAL (STRIKE IT RICH):

ANNOUNCER: It’s the show with a heart, Strike It Rich.

NANNETTA FORREST: Celebrities would go on and try to win money for, like, underprivileged people.

ARCHIVAL (STRIKE IT RICH):

HOST 1: Tom is veteran. His injury makes it impossible for him to do any hard, manual labor.

HOST 2: Well, let’s help him.

HOST 1: Well, all right.

NANNETTA FORREST: Grandpa told me, you can go there, Nan. And I said, go on there with what? And that’s when he pulled out this piece of paper. He told me that my father had been lynched, and that was my first time ever becoming aware of it.

I do wish I had got a chance to get to know him because I often wonder what type of person would I be today had he been in my life. Would I have been the same person? Would I have been a different person? And this is something I’ll never know.

Every now and then, people still bring it up about Cleo Wright getting lynched down South. Had it been done differently, went to court, had a trial or whatever, but it didn’t happen that way.

You did anything that didn’t go along with what they wanted you to go along with, they could lynch you.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

1893

TEXAS LYNCHING

1915

GEORGIA LYNCHING

1919

NEBRASKA LYNCHING

1920

UNKNOWN LYNCHING

NANNETTA FORREST: They didn’t think it was wrong because they didn’t, they didn’t get punished for it for one thing. No, they didn’t.

KEVIN MCMAHON (POLITICAL SCIENCE PROFESSOR, TRINITY COLLEGE): Before the lynching of Cleo Wright, there were 3,842 lynchings in the United States, and the Department of Justice had not fully investigated any of them.

MARGARET BURNHAM (LAW PROFESSOR, NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW: Lynchings clearly violated state law. These were murders, the worst forms of murders.

ARCHIVAL (LYNCH MOB):

NEWS REEL: In the park a yelling mob of 10,000 white. . .

MARGARET BURNHAM: But the states weren’t prosecuting, and lynching was never a federal crime.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

1917

ANTI-LYNCHING PROTEST

1922

ANTI-LYNCHING PROTEST

1933

ANTI-LYNCHING PROTEST

KEVIN MCMAHON: There were movements to pass anti-lynching legislation, but it never became law. So, this is the first time the Department of Justice steps in saying, we’re going to prosecute you. Where in the past, they would just look the other way.

ARCHIVAL (FILM OF BOMBING FROM WORLD WAR II):

NEWSREEL: December 7, 1941.

KEVIN MCMAHON: The lynching of Cleo Wright happens a month and a half after Pearl Harbor.

ARCHIVAL (ANNUAL MESSAGE, 1941):

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT: Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. To that high concept, there can be no end, save victory.

CAROL ANDERSON: This war is being cast as a human rights war against tyranny, racial tyranny, against a regime that is predicated on Aryan supremacy, but there’s a problem. The problem is Jim Crow in the United States.

KEVIN MCMAHON: You have this war against a racist Nazi regime, and the United States is representing itself as a defender of democracy. And if it is a defender of democracy, how can you allow an individual who’s been accused of a crime to be taken from a jail and lynched?

CAROL ANDERSON: Japan looks up and is, like, see? Look at what they do to their own people. And so, the violence raining down on Black people in the United States becomes war propaganda for the Axis nations.

ARCHIVAL (RADIO TOYKO):

A rumor originating in a certain quarters in the United States claims…President Roosevelt…is some kind of a Ku Klux Klan…President Roosevelt also plays upon the loyalty of the colored people…The repeated treacheries against their race for the past years give them very little reason to love him.

KEVIN MCMAHON: This is a crisis of democracy being challenged by a serious foreign threat. And you need to say, well, what is democracy? What’s democracy for African Americans living in the South?

CAROL ANDERSON: You also had this agitation happening in the Black community of remember Pearl Harbor and Sikeston, Missouri. You had one of the premier Black newspapers in the nation launching what was called the Double V Campaign. The Double V Campaign was victory against fascists overseas and against fascists here in the United States. So, Black folks were making the connection that this war for freedom wasn’t just a war for freedom over there. It was for freedom here as well.

ARCHIVAL (SONG):

(LYRICS) If you people will listen to me, from my heart I prayed anew.

For we are Americans.

Praise the Lord.

For we are Americans.

Praise the Lord.

We are Americans.

Praise the Lord, praise his holy name.

MARGARET BURNHAM: After the Cleo Wright lynching, the political imperative to do something about this case was quite strong. So, the Justice Department began to look at two statutes that had been used in the immediate wake of the Civil War to see if they could be applied to lynching situations. Both of these statutes addressed activities to deprive an individual of his or her civil rights.

KEVIN MCMAHON: When you’ve been accused of a crime, you have a right, a federal right, to a trial, and what the Justice Department wants to say is the members of lynch mob have committed the crime of denying Cleo Wright his right to trial. They’ve determined that he is guilty and then carried out the punishment, which is death.

MARGARET BURNHAM: The federal government conducted a fairly wide-ranging investigation, and as investigators sought to find out who was in that mob, no one saw anyone. No one could remember seeing anyone else in that mob. The Justice Department took their case against the lynchers to federal court. The grand jury declined to indict. They rejected the argument that the existing federal statutes applied in a lynching case. So, not getting an indictment had a chilling effect on the federal government’s initiative to use these statutes to address lynching. It’s very, very unfortunate that this case failed. Had the Cleo Wright case been successful, those laws would have been muscular engines to address racial violence.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

APRIL 2020

DENZEL TAYLOR SHOOTING INVESTIGATION

JEAN KELLY: I would imagine there would have been a different outcome if someone was out there trying to tell the cops, don’t shoot him. Please, don’t shoot him. Let him get a chance to explain his side of the story. So, you know, how the law says innocent until proven guilty? Who is the judge and who is the jury to make such decisions in such a quick manner?

ARCHIVAL (KSVS):

NEWS REPORT: Authorities say it could be several weeks before they can piece together exactly what happened on this street in Sikeston.

JAMES MCMILLEN (CHIEF, SIKESTON DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY) : When there’s something like that happens, it’s such a high profile, one of the first things that I do is contact the Missouri State Highway Patrol. They conducted the investigation.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

OFFICER INTERVIEWS FROM INVESTIGATION

OFFICER (CONDUCTING INTERVIEW): We’re going to go over the events that took place Wednesday morning.

DETECTIVE JOSH GOLIGHTLY: I looked up and saw somebody that matched that description that we were given. I could tell that he was holding onto something. I just couldn’t see what it was.

CAPTAIN JON BROOM: We all have our, our weapons out, assuming he’s armed and he just seemed like he was trying to just gain the courage to [BLEEP] pull the gun out and [BLEEP] shoot us, you know. And in, in my mind, he thinks he just killed his damn dad. You know? And what’s shooting a police officer at that point?

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

OFFICER 1: Show me your hands now!

OFFICER 2: Take your hands out of your pockets.

DENZEL TAYLOR: Just kill me, bro.

OFFICER: Now, take your hands out of your pocket.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

TIME ELAPSED AFTER DENZEL RAISED HAND AND BEFORE THE FIRST SHOT WAS FIRED: 1.5 SECONDS

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

OFFICER 2: We got shots fired! We need E.M.S.! We got one subject down. Shots fired!

JEAN KELLY: I seen the body cam. While they were saying, put your hands up, show me your hands, they didn’t give him not even a minute.

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

OFFICER 2: Why didn’t you just take your hand out of your pocket, man?

JEAN KELLY: The protocol is you shoot because you’re feeling in danger, but if they’re not waving a weapon at you, they’re not pointing a weapon at you. There is no reason, no excuse to draw a weapon and shoot someone.

JAMES MCMILLEN: It’s when you feel like that there is a threat to your life or a threat to someone else’s life is when you can use deadly force. Do I think that they intentionally shot him many times just out of meanness or, or… No. I don’t believe that at all. There’s got to be some accountability of not following these commands, and accountability may not be the right word. But nobody wanted this to happen.

HARRY SHARP: This is Smith Chapel Methodist Church, and I came here in 1996 to be the pastor. It was a Black congregation, and when I became pastor of the church, I had no idea that the guy had been dragged right where the church was.

HARRY SHARP (MOTIONING TO AN AREA OUTSIDE THE CHURCH): It would have been right down Osage Street, here.

HARRY SHARP: Cleo Wright was lynched in 1942. That was the year I turned four. I did not hear about it from my parents or grandparents, ever. I asked them about it one time after I had heard about it, but it was not subject of discussion.

MIKE JENSEN: By and large, Sikeston went on as normal. They wanted to put it out of their mind. They wanted to move on. I think that the prevailing mindset at the time was, it’s over and it’s done. Let’s move on.

RHONDA COUNCIL: After you all saw the, the lynching that happened, did you and your friends talk about that?

MABLE COOK: We didn’t talk about it. No. Uh-huh [negative]. There—my Daddy told us not to have nothing to be saying about it. Said it’ll go away if you not talk about it.

RHONDA COUNCIL: It’s got to, kind of, eat you up on the inside of witnessing something like that. You just can’t pretend that it didn’t happen. You can’t. I can’t say I can just easily get over it. Now, I wasn’t there when it happened, but it has an effect on my grandmother. She’s a part of me. I’m a part of her.

LARRY MCCLELLON: I used to ask Mom, you know, what is it with this man that supposedly got lynched? And she told me, don’t you ask no questions about Cleo Wright. She knew what it was all about, and she didn’t want to take no chance of that happening to me. Young, white ladies used to come out to my house and blow the horn for me. My mom would tell them, you all go on back up town. I don’t want my son to get in no trouble. See, I didn’t cross the line because I knew what was waiting any time you get caught up in something like that. I knew what time it was here in Sikeston, Missouri.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

SPRING 2020:

PROTEST AFTER DENZEL’S DEATH

ARCHIVAL:

PROTESTOR: He didn’t have no weapon, and they shot him anyway.

LARRY MCCLELLON: It’s hard to get my people to protest.

MIKELA JACKSON: I wasn’t satisfied with how we protested. The world, they have no idea who Denzel Taylor is. They have no idea he got shot 19 times by police officers, from chest on down to his legs.

ARCHIVAL:

PROTESTOR: Hands up! Don’t shoot!

MIKELA JACKSON: When we did the protest for Denzel, we wanted them to feel our pain.

ARCHIVAL:

PROTESTOR: They’re trying to kill all of us.

MIKELA JACKSON: But the protest didn’t do much.

LARRY MCCLELLON: It’s a funny thing. It just washed away in the rinse. You didn’t hear anything else. You know, some of our own people, they have a problem when they see you speaking out regarding an issue like that.

ARCHIVAL (GEORGE FLOYD PROTEST):

PROTESTORS: Police violence no more!

LARRY MCCLELLON: And when all this stuff was going on about George Floyd worldwide, Sikeston stood pat. Nothing. Sikeston, they’re stuck in times, and they’re just afraid of things that has happened right here in this town. They don’t want trouble to arrive. I tell them, hey, you can speak out and support whatever we’re trying to do. But it doesn’t hardly reach first base. They say right now that we’ve come a long ways, but we haven’t really came a long ways because they are still shooting us down every day. And I, and—so, it gets, it gets next to me.

CAROL ANDERSON: When I think about the line that goes from the way policing worked in the past to what we’re seeing today, it is that you’ve got a system that says, you’re guilty before you’re innocent. Lynching created a narrative that Black people were so criminal that they did not deserve to go through the justice system. They deserved whatever punishment that the community could mete out to them.

MARGARET BURNHAM: The inability to talk about these events generated enormous trauma for those who witnessed them, and that trauma was carried across the generations.

RHONDA COUNCIL: I can’t even imagine what my grandmother saw or what the whole Sunset community saw at that time. Nobody deserves to be lynched. I don’t care what you did. If they arrested him, that was fine. But then to drag him through the streets? That was so wrong.

KEVIN MCMAHON: It’s easy to, sort of, be outraged if somebody who was innocent of a crime gets lynched. If you want to defend the right to a trial by jury, it’s got to be for everyone, not just those who you think are innocent.

CAROL ANDERSON: The people who yanked Cleo Wright out, nothing happened to them, and we see that moving forward. The lack of accountability in policing for killing Black people, that ability to hold life and death in your hands with impunity.

MARGARET BURNHAM: Although there have been many changes in the law, what lingers in our legal system from 1942 is really our inability to control police violence against people of color.

MIKELA JACKSON: The officers was put on leave, and they returned back to work after that. They was not on leave long at all.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

JULY 2020

THE INVESTIGATION CONCLUDED THAT THE SHOOTING WAS JUSTIFIED BECAUSE “IT WAS REASONABLE FOR THE OFFICERS TO FEAR” THAT DENZEL WAS ARMED AND INTENDED TO SHOOT THEM.

MIKELA JACKSON: I feel like had they tazed Denzel or just did matters completely different, Denzel would have had his day in court. Denzel would have been able to tell his side of the story.

JEAN KELLY: I obtained a lawyer and I just say it’s a moral standard for me to seek justice. I hope that the police officers, the chief of police, I hope they have a wake-up call, and I want them to be cognizant of what they are to do when they put on their uniforms and they get their weapons and they’re out to protect people, and not to kill people.

MILTON TAYLOR: I was angry. I was very angry at Denzel. I was angry until I saw that video. When I saw that video, my anger just went away, and I, I began to cry, and— they took away my chance to make amends with my son. They was supposed to come there and diffuse the situation, and they made it worse.

MIKELA JACKSON: Denzel needs justice, just like any other person who has been in Denzel’s situation.

RHONDA COUNCIL: This, according to Cleo Wright’s death certificate, is where he was buried. And I do wish he had some kind of acknowledgement out here. We can’t help what our ancestors did in the past. We can’t help that, but I would like for just one white person to acknowledge and say this happened and for them to say they’re sorry as well.

LARRY MCCLELLON: It’s a major problem because they know what they’ve done. They don’t know how to start the healing process.

HARRY SHARP: I would like some magic fairy dust to heal this community. I don’t know what it is, but there are always people that would say, see how bad the white people were? And make that meaning “are.” I have no question there were some bad people involved with that lynching, but let’s don’t paint everybody with that brush.

MIKE JENSEN: I think there remains a level of communal shame, communal regret, and I can’t justify it. But let’s let a sleeping dog lie. I mean, come on. What is served by talking about this? Okay? Will it change our community? Will it, will it improve race relations in our community? It’s legitimate to say are you really trying to grind down to zero or are you just picking a scab.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

JUNE 2021

PERSHARD OWENS (EDUCATOR, LINCOLN UNIVERSITY EXTENSION PROGRAM): Hello, everybody. My name is Pershard Owens. Juneteenth is something important that we have not been taught while we were growing up. It’s time for us to stop expecting other people to educate our kids on our history, and it’s time for us to start stepping up and doing it on our own.

There is something deeply embedded in Sikeston that needs to be uprooted, and that way, we can move forward. The fact remains that this African-American man was burned in front of a church and we don’t talk about it. When I saw the video of Denzel Taylor, when that got released, that hurt me because that could have been me.

ARCHIVAL (POLICE BODY CAMERA):

POLICE OFFICER: We need E.M.S. We’ve got one subject down. Shots fired.

PERSHARD OWENS: That could have been my nephew. That could have been my brother, and, um, you know, it’s just hard. I want people to understand that not all Black men are a threat. I’m a person just like the next person is, and, you know, when you see stuff like that happen, it’s just, like, okay. What do we do to change it?

JAMES MCMILLEN: You know, the video is out on social media. I had never really considered myself to have any prejudice or bias.

JAMES MCMILLEN (SPEAKING TO PEOPLE AT A TOWN EVENT): How you all doing?

JAMES MCMILLEN: But I came to Sikeston to work as a police officer, and some of my first calls in the Black community were dealing with drug dealers and people in shooting cases and stuff like that. I started thinking, I don’t have anything in common with these people and just unfairly judged the whole community off those few experiences. So, case by case, you know, it didn’t happen overnight, but I started to learn how, really, I had that wrong.

JAMES MCMILLEN (SPEAKING TO PEOPLE AT A TOWN EVENT): Where do you preach at?

JAMES MCMILLEN: I think that our failure at times is that we don’t really consider ourselves as an entire community. We’ve got to be willing to look at and just say how can we better this?

TEXT ON SCREEN:

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA

IN OCTOBER 2021, A GROUP FROM SIKESTON TRAVELED TO THE NATIONAL MEMORIAL FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT LYNCHING.

PERSHARD OWENS: I came here looking for truth. I wanted to know more about the lynchings that I never was taught in school. I want to know all of the history. I don’t want a watered-down version of it. In the museum, one of the things that was written on the wall was, “Slavery, it didn’t end. It just progressed.” Bringing more awareness to Cleo Wright is going to upset a lot of people. In Sikeston, there is so much tradition. At some point, you just have to say, you know what? If it pisses you off, it is what it is. It’s the truth and we need to talk about it.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

JANUARY 2022

80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CLEO WRIGHT LYNCHING

CHURCH CHOIR (SINGING): Glory, glory, hallelujah, as I lay my burden down.

PASTOR KYLE PERNELL: We are honored and humbled to serve as instruments in the remembrance service for Cleo Wright.

PERSHARD OWENS: While we are all here gathered for such a horrible crime that was done, we have to remember that things cannot change unless it’s us who do it, and the song I’m going to sing is called “A Change is Gonna to Come.” And that change is gonna come.

PERSHARD OWENS (SINGING): I was born by the river. In a little tent. And just like the river, running and running, I’ve been running ever since. It’s been a long, long time coming, but I know change is going to come. Oh, yes, it is.

RHONDA COUNCIL: The African American community has always been silenced for fear of something possibly happening to their family or to themselves, but right now, we are giving Cleo Wright a voice. I never in a million years thought this would happen. My grandmother Mabel and my Aunt Carleen unfortunately passed away not even a year apart. And I hate that she could not have seen this. I hate that she could not have seen this happen because she had kept that story to herself for so long. To be able to say it, to be able to tell it, this is just so amazing, so amazing. She’d be so happy.

MICHAEL HARRIS (PASTOR, OPEN DOOR FELLOWSHIP OUTREACH MINISTRIES): Sikeston has some history we still have yet to work towards resolving. The lynching of Cleo Wright, it shaped the mindset of how we as citizens of Sikeston respond to one another. I was trying to pull out all the topsoil that I could so that we can have some clean fill when we get ready to put into the jars. I think this will, kind of, capture the essence of the occasion.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

IN JUNE, 2022, THE COMMUNITY COLLECTED SOIL FROM THE SITE WHERE CLEO WRIGHT’S BODY WAS BURNED.

THE SOIL WILL BE DISPLAYED AT THE NATIONAL MEMORIAL FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE.

MICHAEL SNIDER (GRANDSON OF NANNETTA FORREST): Once I got to Sikeston, I was welcomed with open arms because I was Cleo’s great-grandson, and I didn’t realize what kind of impact it had on the town until I got here. It scarred Sikeston. Even the newer generation can see that something was wrong. Something’s wrong here.

PASTOR KYLE PERNELL: How do offer a prayer when there are so many different emotions and things going on? The Bible says that the Lord spoke to Cain and said, “The blood of your brother is crying out from the ground unto me.” And the blood is still crying out. It’s been crying out, but nobody has been echoing what it’s been saying until now.

MICHAEL SNIDER: It’s a victory over that mental slavery. Once we were able to break through the mental chains, people started voicing. They started asking questions.

MICHAEL HARRIS: You all keep coming. Any, any jar.

MICHAEL SNIDER: It’s the beginning of acknowledgement, and that being quiet isn’t the answer. It’s still tragic, but we can actually talk about and express how we feel about it in the open. So, instead of an apology, I’d rather see change. I’d rather see a more positive turn in life for the community that has such a tragic history.

TEXT ON SCREEN:

IN FEBRUARY 2024, THE CITY OF SIKESTON SETTLED THE DENZEL TAYLOR WRONGFUL DEATH LAWSUIT FOR $2 MILLION.

THIS FILM IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MABLE COOK, CARLEEN HARRINGTON, AND NANNETTA FORREST.

(END)

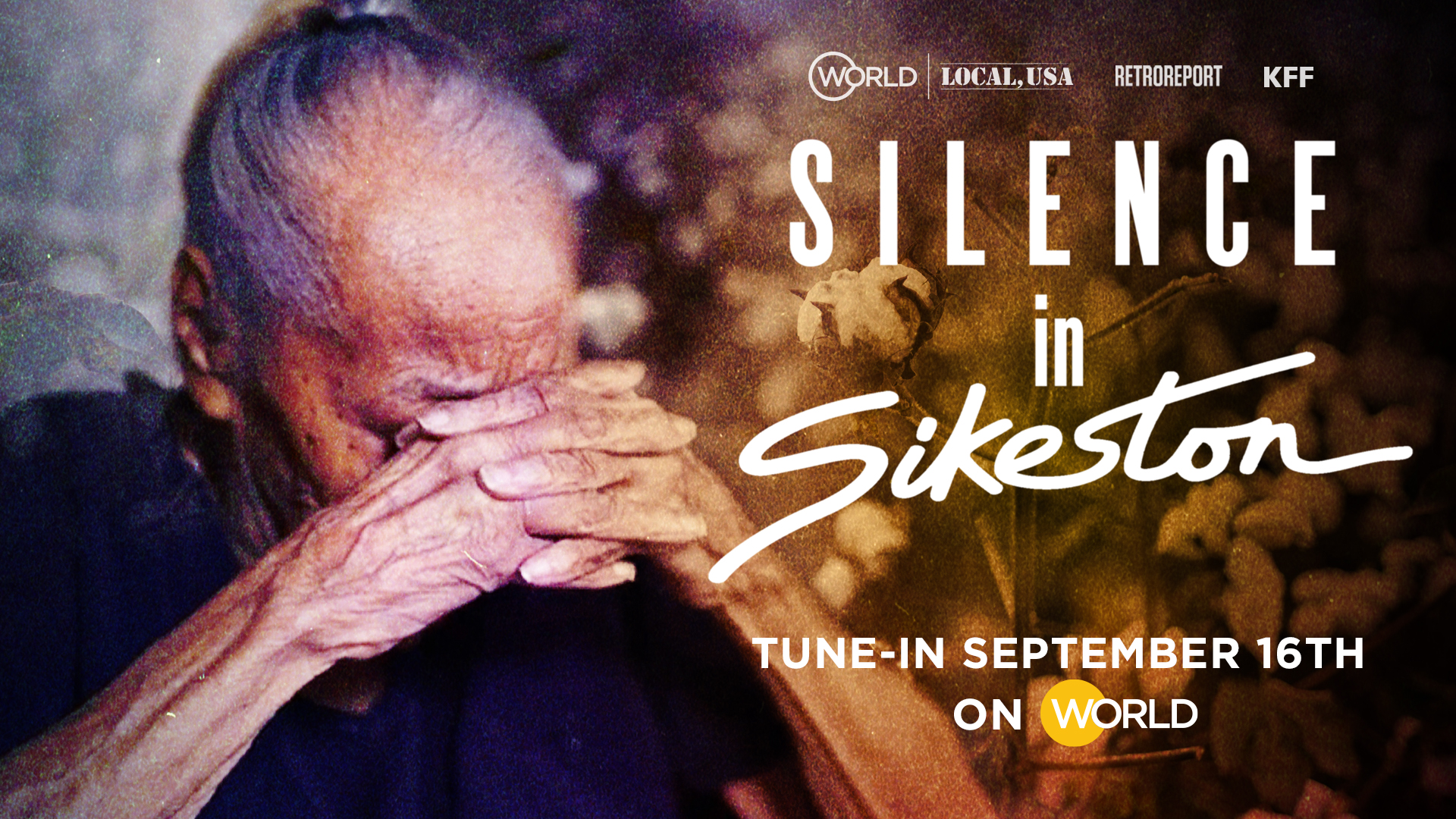

Silence in Sikeston

The story of how the 1942 lynching of Cleo Wright – and the subsequent failure of the first federal attempt to prosecute a lynching – continues to haunt the small city of Sikeston, Missouri. Then, in 2020, the community is faced with the police killing of a young Black father. The film “Silence in Sikeston” explores the necessary questions about history, trauma, silence and resilience over 78 years.

The companion podcast is about finding the words to say the things that go unsaid. Hosted by Cara Anthony, a KFF Health News Midwest correspondent and an Edward R. Murrow and National Association of Black Journalists award-winning reporter from East St. Louis, Illinois.

“Silence in Sikeston” is a co-production of Retro Report, WORLD and KFF Health News. To see more check out our “Silence in Sikeston” collection.

Stay up to date. Subscribe to our newsletters.

- Director / Writer: Jill Rosenbaum

- Reporter: Cara Anthony

- Editor: Cheree Dillon

- Editor: Brian Kamerzel

- Senior Producer: Karen M. Sughrue