In January of 1982, in the midst of El Salvador’s civil war, photographer Susan Meiselas and I clandestinely crossed the border from Honduras to begin a reporting assignment behind guerrilla lines.

Traveling at night to avoid detection by Salvadoran troops, leftist guerillas eventually brought us to a small village — El Mozote. The horrifying sights of a massacre, even the smell of death, were unavoidable — burned bodies beneath collapsed, charred beams of destroyed houses; skulls; children’s toys; makeshift graves. The only survivor, Rufina Amaya, recalled hearing from her hiding place the pleas of her young son before he and her three daughters were machine-gunned to death — one was only eight months old; her blind husband was also executed.

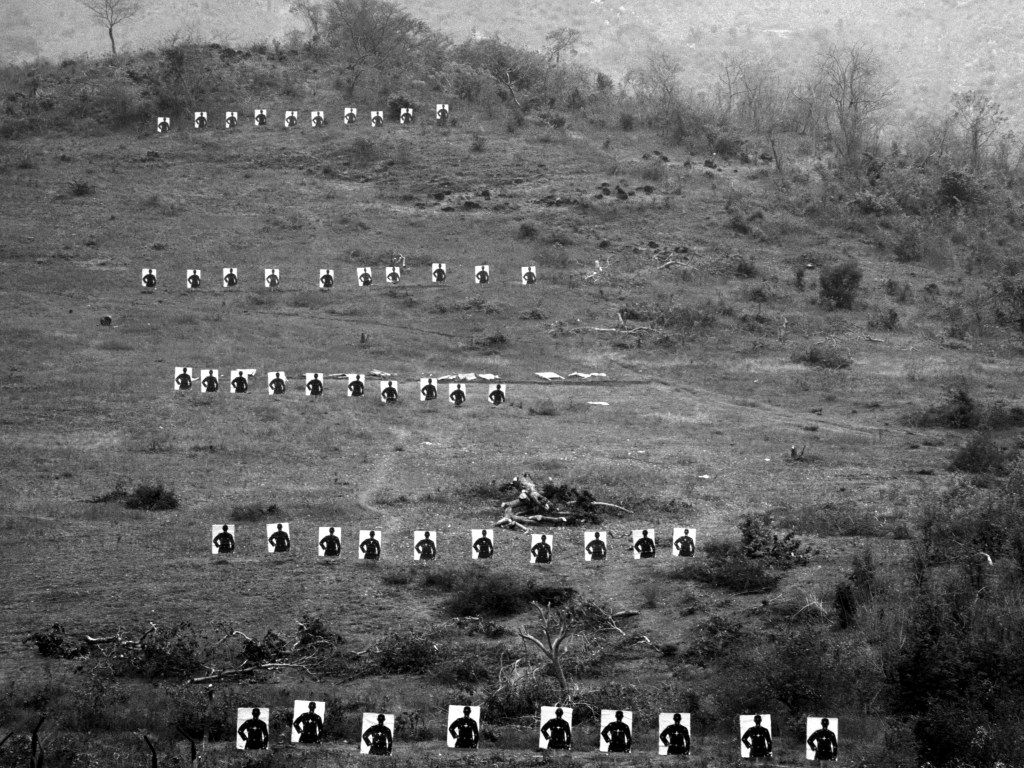

The perpetrators were members of a U.S.-trained Salvadoran counterinsurgency unit called the Atlacatl battalion. Fresh from a skirmish with the guerillas, they had entered El Mozote in December 1981, and begun a systematic campaign of rape, plunder, torture and murder. In this village — little more than a Catholic church in a simple town square — more than two hundred men, women and children were killed; only Amaya had survived. Altogether, some 800 were killed in the area, making “El Mozote” a name that stands in infamy, one of the worst massacres in modern Latin American history.

The Salvadoran government denied the killings had occurred and the Reagan Administration insisted that The New York Times and The Washington Post reports of the massacre were gross exaggerations. As one Reagan official told a congressional subcomittee,“no evidence could be found to confirm that government forces systematically massacred civilians.”

But twenty years later, the United Nations Commission on the Truth for El Salvador conducted a thorough investigation, and confirmed what we had reported. The commission wrote:

“During the morning, they [the Salvadoran soldiers] proceeded to interrogate, torture and execute the men in various locations. Around noon, they began taking out the women in groups, separating them from their children and machine gunning them. Finally, they killed the children. A group of children who had been locked in the convent were machine-gunned through the windows. After exterminating the entire population, the soldiers set fire to the buildings.”

In 2012, the president of El Salvador acknowledged the government’s responsibility. “In three days and three nights, the biggest massacre of civilians was committed in contemporary Latin American history,” said President Mauricio Funes, wiping away tears while speaking to a crowd in El Mozote. “For this massacre, for the abhorrent violations of human rights and the abuses perpetrated in the name of the Salvadoran state, I ask forgiveness of the families of the victims.”

SUSAN MEISELAS joined Magnum Photos in 1976. She is best known for her coverage of the insurrection in Nicaragua and her documentation of human rights issues in Latin America. The recipient of numerous awards, including the Hasselblad Foundation Photography Prize (1994) and the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Award (2005), her work has been exhibited at the Bibliothèque Nationale Paris, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Art Institute of Chicago. Meiselas was named a MacArthur Fellow in 1992. View her work at www.susanmeiselas.com.

RAYMOND BONNER is a contributing reporter to Retro Report. He is a lawyer turned journalist, who has worked as an investigative reporter and foreign correspondent for The New York Times and as a staff writer at The New Yorker. He has received numerous awards, including the Louis M. Lyon Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University; and the Latin American Studies Association Award for reporting from Central America.

RELATED:

First-Hand Account: Lessons From the El Mozote Massacre by Clyde Haberman

The High Price of Doing Journalism in El Salvador by Nelson Rauda